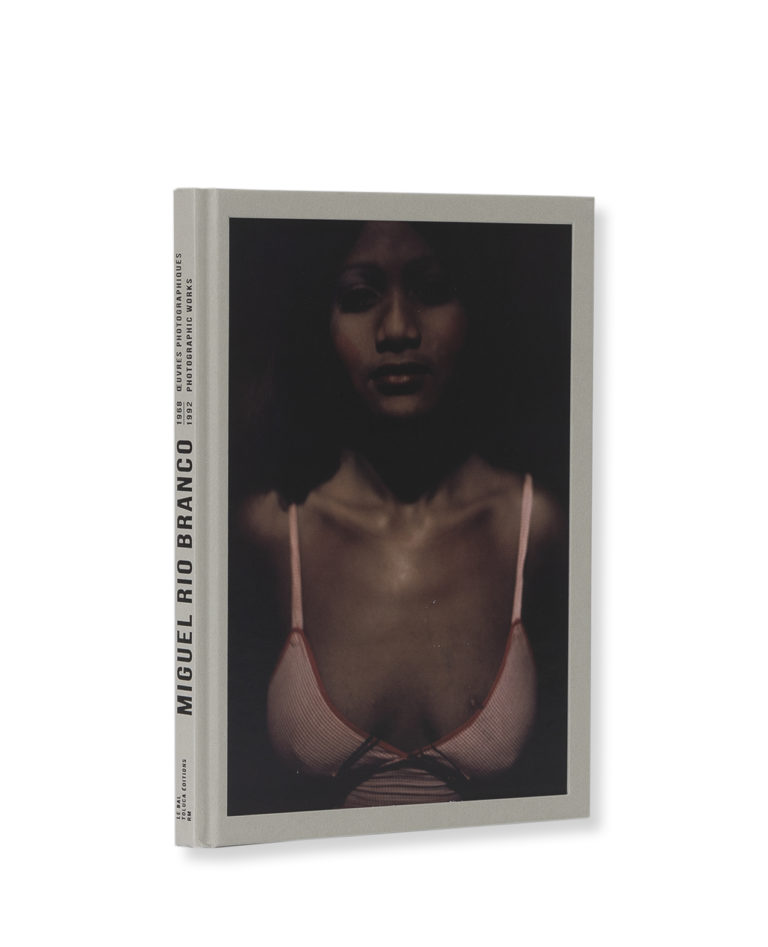

The photographs of Miguel Rio Branco, as Jean-Pierre Criqui notes in the text accompanying the hundred or so images that make up the work,

“offer us a vast catalog of subjects, assembled through a sensitive eye attuned to the aesthetic transformation of the most humble or vile motifs. (Baudelaire on the ragman in Artificial Paradises, 1860: ‘Everything the big city has rejected, everything it has lost, everything it has disdained, everything it has broken, he catalogs, he collects, gathering the archives of debauchery, the jumble of refuse. He sorts through it all, making an intelligent selection. He gathers, like a miser his treasure, the rubbish which, digested by the divine Industry, will once again become objects of utility or pleasure.’)

Excess is what characterizes the subject here, in the “asphyxia” that Miguel Rio Branco speaks of in relation to photography: an excess of life surging in all directions, and death at work, representing its inseparable reverse side.”